Neuroprosthetics, an interdisciplinary field merging neuroscience and biomedical engineering, has steadily evolved over the past century, transforming the lives of people with physical limitations. From early electrical stimulation experiments to today’s sophisticated brain-computer interfaces, neuroprosthetics stands as a testament to human ingenuity in the quest to restore and enhance bodily functions.

Early Beginnings (1700s–1800s)

The roots of neuroprosthetics can be traced back to experiments with electricity in the late 18th century. Scientists like Luigi Galvani discovered that electrical currents could stimulate muscle contractions in frog legs, laying the foundation for understanding the nervous system’s electrical nature. While limited to theory, these experiments were the first to suggest that electricity could influence biological function.

The First Implanted Devices (1950s–1970s)

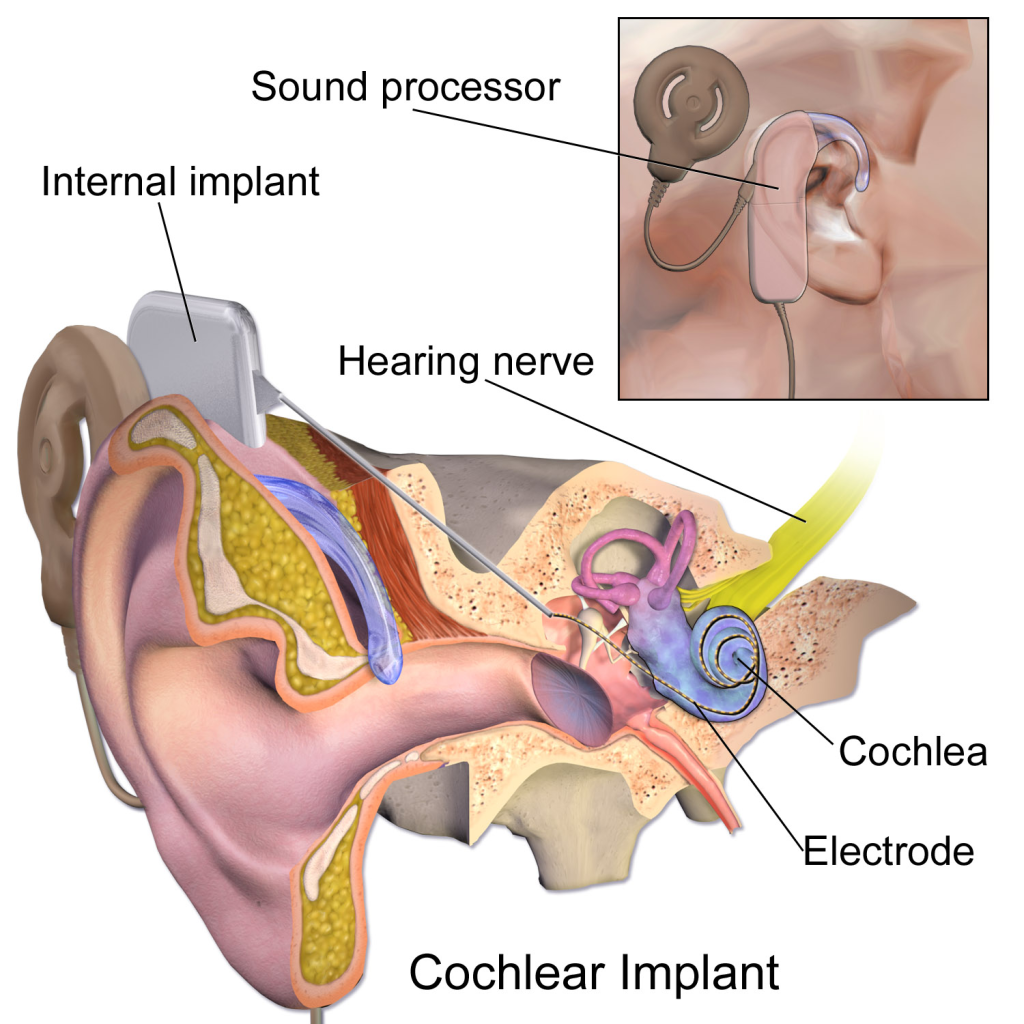

The 1950s saw the first practical neuroprosthetic applications with the development of the cochlear implant, designed to restore partial hearing to the deaf by directly stimulating the auditory nerve. Around this time, functional electrical stimulation (FES) devices emerged, allowing for basic limb movement in people with paralysis through direct muscle stimulation.

Expanding Horizons with Brain-Computer Interfaces (1980s–2000s)

In the 1980s, neuroprosthetics advanced as researchers explored brain-computer interfaces (BCIs), systems that enable direct communication between the brain and external devices. Breakthroughs in recording electrical signals from the brain allowed paralyzed individuals to control computers or robotic limbs with thought alone. Scientists like Dr. Philip Kennedy pioneered electrode implantation in the brain, allowing for increased control over assistive devices.

Modern Advances: Closed-Loop Systems and Sensory Restoration (2010s–Present)

The past decade has witnessed incredible growth in neuroprosthetic technology. Innovations now focus on “closed-loop” systems that can send signals from the brain to a prosthetic limb and receive sensory feedback in return, mimicking natural movement and sensation. Today’s neuroprosthetics, like the advanced robotic limbs developed at DARPA and BrainGate’s cutting-edge BCIs, have redefined possibilities for sensory restoration, helping people regain complex functions and autonomy.